Artist and researcher C. Mehmet Kösemen's new book, Osman Hasan and the Tombstone Photographs of the Dönmes, documents tombstone portraiture belonging to Crypto-Judaic graves from between the 1880's and 1940's, which he found to be carrying the signature of Osman Hasan. Kösemen answered our questions regarding this unique and secretive culture, his project's process of development, and his feelings towards taking cemetery strolls.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Can you talk to us about the state of mind that led you to the graveyards in the first place and how that changed throughout the project's development? What is it like to stroll among cemeteries?

The story of this book began three years ago, when in a moment of crisis, I entered the Thessalonians cemetery in Bülbülderesi – a bit out of curiosity, and a bit to overcome my fear of death. Strolling through cemeteries is already a strange feeling, however, walking through graves that are adorned with strange symbols, monuments covered in moss, and centuries-old trees, like in Bülbülderesi, is a surreal experience. As I walked, death started to seem less like something to be feared, but more like a fantastic adventure that will come to everyone.

This community holds idiosyncratic, different, and secret beliefs. That's why, in Bülbülderesi, I saw symbols, patterns, and architectural shapes that are very different from other cemeteries in Turkey. Once my cemetery trips passed the phase of being curious strolls and turned into serious research, I discovered many different symbols at Bülbülderesi, as well as other Thessalonian cemeteries. For example, some tombstones were built with a highly consistent art-deco style, with patterns of leaves and arcs. At other graves I saw highly intriguing butterfly reliefs with almost anthropomorphized faces. These are clearly the symbol of a transformation, of some sort of a metamorphosis. However, I reckon that only those who are lying in those graves know the exact meaning of these symbols.

What was it that drew you to these particular tombstones and what were some of the differences that you observed? You also include different motifs and carvings in your book; can you tell us about the meaning behind these images and the research process?

Bülbülderesi is the cemetery of Crypto- Jewish, dönme, families that emigrated from Thessaloniki.

When did you start to think that this could or should be a project in its own right? How did the book start to take shape?

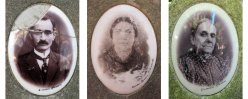

Some of the tombstones at Bülbülderesi are adorned with sepia-toned photographs printed onto porcelain plaques. Especially the portraits belonging to those who died between the 1890's and late 1930's, appear to be placed onto their graves in a highly delicate fashion. Most of them bare an interesting signature: “Osman Hasan.” After touring Bülbülderesi, I entered another Thessalonian cemetery, this time in Maçka. I was saw Osman Hasan's signature there, as well. I became very curious and started searching on the Internet and in books on the history of photography in Turkey. There was no trace of him anywhere. I said, “Okay, we're faced with a forgotten photographer, who no one has heard of before.” Then, I started photographing all of the tombstone pictures that belonged to Osman Hasan.

During the Gezi events, some of the hooligans taking refuge at the cemetery in Maçka broke some of the porcelain tombstone photographs. The digital photographs of them that I had, were the last traces of these people who had died, as well as this mysterious artist. After this stage, my decision to turn this project into a book became definite. I organized the photographs that I had and re-took some of the ones that were missing. I contacted a friend who could be considered the Thessalonian community’s archivist and through him, I met a living relative of Osman Hasan. Through this relative, I then discovered other cemeteries with portraits belonging to Osman Hasan and visited and researched those locations; the collection of photographs got even bigger. After visiting so many cemeteries, I was also in possession of many photographs depicting cemetery architecture and symbolism, and I included these in the project, as well. I started reading all of the notable books on Thessalonian Dönmes and Sabetay Sevi. At the last minute, large cardboard pictures belonging to Osman Hasan were found among the estate of a Thessalonian family and this last surprise had me very excited. It took a few months for me to organise all of the data I had collected and write the text of the book.

Normally, for book projects, an offer is prepared beforehand and if the publishing house approves, a contract will be signed and the book written. This project did not happen that way; with the courage of insanity, I prepared a draft of the book and sent it to publishing houses. Fortunately, one of the prominent history publishers, Libra Yayınları, wanted to publish the book. With the patient support and guidance of Libra Yayınları's owner Rıfat Bali, it took a few more months to get the book to its final state. Finally, at the beginning of August, Osman Hasan and the Tombstone Photographs of the Dönmes was on the market.

Could you share some of what you learned regarding Dönme culture and tombstone portraiture throughout this process?

For years, Thessalonian Dönmes were seen as unreliable, hidden traitors, and were fodder to countless conspiracy theories. There is probably no other group in Turkey who Leftists, Nationalists, Islamists, and even some Jews could all defame with such ease. With this research, I had the opportunity to document the last traces of the Dönmes' completely unique architectural culture, world of faith, and literature. Since this book is in English, I was able to share this hardly known, misunderstood, and exhausted community and the legacy of Osman Hasan, one of this community's artists, with the whole world. It would be hard to find a more satisfying feeling. I hope that this book will help Dönmes be understood as regular people with interesting and distinctive elements belonging to the East Mediterranean, rather than monsters living in conspiracy theories.

As much as you know, can you tell us about the technique Osman Hasan utilized for these portraits?

Osman Hasan is a very talented photographer and artist. According to the information we obtained from his relative, he developed many of his own unique techniques. For example, back in the day, apparently only a few studios in Italy would print photographs on porcelain plaques and those who wanted the procedure, would have to mail the photographs to Italy and wait for the porcelain plaques.

While he was living in Thessaloniki, probably through information he received from Greek or Italian masters, Osman Hasan developed his own system of printing. In fact, as a mark of this special procedure, all of the pictures with Osman Hasan's signature bore a purple-ish tone.

What were some of the things you were paying attention to while documenting these portraits?

I tried to fully document who the portraits were of, their dates of birth and death, as well as their vocational information, if available. Since many headstones have old Turkish letters, I then had them translated. However, some had become so indistinct that it wasn't possible to do so. At some gravestones I found interesting symbols or long, poetic epitaphs, which I transferred to the book in detail.

Are you considering expanding this project, perhaps outside of Istanbul?

I think this project may have ended here, but I'm sure there are more works by Osman Hasan hiding in some corners.

I would have liked to include the Izmir / Kokluca cemetery where my own family members are buried, as well as a few other locations outside of Istanbul. After this project, however, I would like to work on something regarding the other minority cemeteries in Istanbul. Armenian and Roman Catholic communities have highly impressive cemeteries that look like art and sculpture museums.

The book is being sold at a fairly high price. How many copies were printed and what were the factors that affected pricing?

This is a 550-page color printed book and even though it contains things that will appeal to everyone, unfortunately, it is about a very limited, niche topic. That's why at a high price of $300 it can only just recover costs. A book like this is mainly purchased by international libraries and research institutes. So far, it's been purchased by corporate clients from the U.S., Europe, and Israel. Surprisingly, some of the members of the Thessalonian families also showed a great interest in the book and purchased it. Readers in Istanbul can find the book at the bookstores Pandora and Eren.

In regards to reactions to the book and its reach, what are some of the developments that have surprised you the most?

Since it's currently still a new book, reactions have been limited. However, the greatest reaction came from the author of the book Salonica, City of Ghosts, Columbia University history professor Dr. Mark Mazower. He praised my work, saying “You have given new life to this community.” Known psychotherapist Irvin Yalom was also very affected by the book and allowed me to use a quote from his work, Love's Executioner, for the introduction. I also gave many interviews to newspapers and forums overseas, so I think there will be other interesting developments in the future :)

Some of the portraits in your book have been damaged, either by time itself or through human intervention. However, regardless of the fact that they've been erased or broken, they continue to carry a sense of permanence, which is important to preserve. As someone who's undertaken such a project, what are your thoughts on tombstone portraiture as a tradition and what it leaves behind?

Tombs and tombstone portraits are built and created with a sense that they will last forever, but they are as mortal as everything else. The cracks, fractures, and scratches on Thessalonian tombstone portraits are affecting marks of the disproportionate hate this misunderstood community were subject to in Turkey. At the same time, the pictures are also exposed to the effects of time. Some lose the black paint in their eyes and assume surreal forms reminiscent of spirits. Both people and time are factors that are just as perennial for the story of the Thessalonian Dönmes as the portraits themselves.

Today, there are portraits atop many graves, and every grave with a photograph does not belong to Thessalonian Dönmes. However, these pictures, taken by Osman Hasan and produced between the 1880's and 1940's, are one of the lasting legacies of this mysterious community.